- In the current issue of Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Helena Milton and Hugo Mercier review some of the research on cognitive obstacles to pro-vaccination beliefs.

- Vox on How our housing choices make adult friendships more difficult.

- From the Economist: Africans are mainly rich or poor, but not middle class.

- Jonathan Haidt et al. respond to a recent critique of Moral Foundations Theory.

- The 50 most critical scientific & technological breakthroughs required for sustainable global development.

- A new paper in PLoS ONE develops a method for learning the relative preferences of individual from their histories of choices made.

- (HT Chris Blattman) Scientists who found gluten sensitivity evidence now shown it doesn’t exist.

The impact of watching Earthlings is smaller than you think

by Bobbie

Every vegetarian is regularly faced with the question, “what made you go vegetarian?” Overwhelmingly, the response I hear follows more or less the same logic: “I watched/read X and just couldn’t imagine eating meat ever again” (where X is a documentary or book such as Earthlings, Food Inc., Speciesism, The Ethics of What We Eat, …).1

This “critical juncture” — or “conversion experience” — explanation feels true to many vegetarians. After all, their meat consumption is dramatically lower today than it was before watching Earthlings, and they also eat much less meat than the large proportion of the general population that has never seen the documentary.

However, these simple “before/after” and “between group” comparisons wildly over-estimate the true causal effect of watching Earthlings, which is defined as the difference between your meat consumption today and what it would have been if you had not watched Earthlings (while everything else remained unchanged). The fact that we cannot directly observe this counterfactual is the fundamental problem of causal inference. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) solve this problem by randomly allocating subjects to watch Earthlings or some “placebo” documentary, which ensures that in large enough samples the treatment and control groups are identical on all characteristics except for the fact that one group watched Earthlings and one did not.

In this post, I argue that the true effect of watching factory farming documentaries is much smaller than many animal advocates think. Nevertheless, these documentaries may still be an effective advocacy tool, especially if they help vegetarians have larger spillover effects on friends and colleagues. Ultimately, what is needed is much better evidence on the effects of these documentaries across different sub-populations and evidence on whether such spillover effects exist.

Would you have still become vegetarian if you had not watched Earthlings? Probably.

In the real world where watching Earthlings is not randomly assigned, the kind of people who choose to watch Earthlings are likely to be very different than the people who do not. In particular, people who watch Earthlings are likely to already be much more sympathetic towards animal welfare and may already be experiencing a downward trend in meat consumption. As a result, simple comparisons between the people who have watched Earthlings and those who have not will result in biased estimates of the true causal effect. Similarly, simple before/after comparisons of a person’s meat consumption before and after they watched Earthlings will be biased if they were already on a downward trend in meat consumption, or if something else happened around the same time that led them to change their meat consumption (e.g. change in their social network, change in accessibility of vegan products).

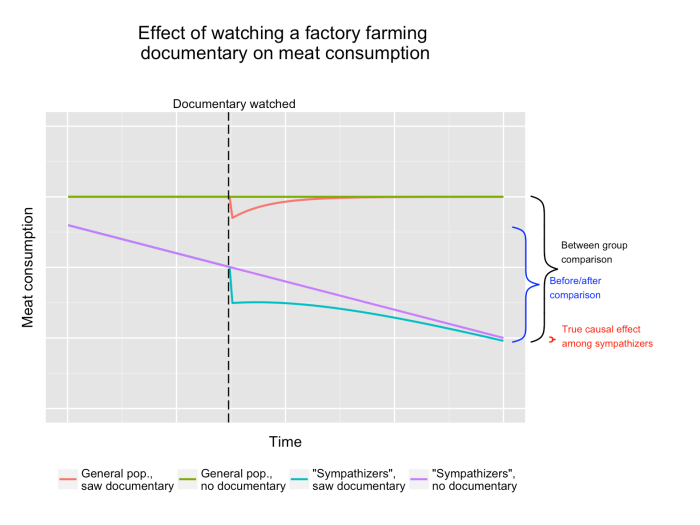

These biased estimates of the true causal effect are illustrated in the figure below, which divides the population into two groups: “sympathizers” who are already sympathetic to animal suffering on factory farms, and the remainder of the general population who are not.

The purple and green lines show the trends in meat consumption over time for sympathizers and the general population if they did not watch Earthlings. Conversely, the turquoise line represents what would have happened to the meat consumption of sympathizers if they had watched Earthlings, and the red line represents what would have happened to the meat consumption of the general population if they had watched Earthlings.

This figure is meant to communicate three testable hypotheses. [Note: this figure is based entirely off of my own priors, rather than real data.]

1. Short-term effects fade over time.

First, if we just look at the short-term effects of watching Earthlings, there seems to be a substantial effect on meat consumption among both sympathizers and the general population. For sympathizers, this can be seen in the sudden dip in the turquoise line after watching Earthlings, such that the causal effect is the gap that this creates between the purple and turquoise lines. For the general population, this can be seen in the sudden dip in the red line relative to the green line.

However, for both of these populations, the effects fade over time. In the general population, the meat consumption of people who watched Earthlings increases back to its original level as the salience of the documentary fades over time. Among sympathizers, the short-term effect of watching Earthlings fades as the long-term trend in meat consumption catches up. In other words, watching Earthlings merely accelerates the transition to vegetarianism among sympathizers (without any lasting long-term effects), while in the general population there are no long term effects.

2. Before/after and between group comparisons over-estimate the true effect.

Second, both the before/after comparison and between group comparison greatly over-estimate the true causal effect of watching Earthlings. In the general population, the true long-term effect of watching Earthlings is zero, since there is no gap between the red and green lines. Among sympathizers, the effect of watching Earthlings also converges to zero over time as the turquoise line converges with the long-term trend in meat consumption (purple line). However, both the before/after and between group comparisons would result in much larger (and therefore biased) estimates of treatment effects, as shown in the figure.

3. The short-term effect is larger among sympathizers than among the general population.

Third, the short-term dip in meat consumption is larger and lasts longer among sympathizers than in the general population. This hypothesis isn’t very consequential if the long-term effect of watching Earthlings is zero in each group anyways, yet it is nevertheless a testable hypothesis and has implications for the generalizability of studies conducted on sympathizers. Specifically, any RCT conducted on a sample of sympathizers that finds encouraging short-term effects on meat consumption must be taken with a grain of salt, since it seems likely that even these short-term effects would be smaller (and fade faster) if the study were replicated in the general population.

Assumptions

These three hypotheses rest on at least three important assumptions.

Assumption 1: I’ve assumed that vegetarians have no spillover effects on non-vegetarians. However, in reality, a sympathizer who watches Earthlings could have spillover effects on the meat consumption of friends/colleagues through at least two different mechanisms.

First, by accelerating the transition to vegetarianism among sympathizers, watching Earthlings creates more time for vegetarians to have spillover effects. Assuming that non-vegetarians are more likely to reduce their meat consumption the longer they are exposed to vegetarians (rather than having backlash effects), then watching Earthlings will have a greater overall effect on meat consumption than I’ve argued in the figure above.2

Second, watching factory farming documentaries could have spillover effects by strengthening the conviction and ability of sympathizers to expand the animal advocacy movement. For instance, the documentary Speciesism walks viewers through the problems with different justifications for eating certain animals but not others (e.g. pigs vs. dogs). Even if this has no long-term causal effect on the viewer’s own trend in meat consumption, it may empower them to spread the animal welfare message more effectively.

Assumption 2: I’ve ignored the possibility that there exists some small fraction of the population that really was dramatically affected by watching Earthlings, and that their perceptions of this causal effect are not biased by the flawed before/after or between group comparisons I’ve described above.

I’m willing to accept that there are some people in the general population who were not very sympathetic to animal suffering before watching Earthlings (i.e. they had a flat pre-documentary trend in meat consumption), but were somehow randomly exposed to Earthlings and then dramatically reduced their meat consumption over a sustained period. For these people, the true effect of watching Earthlings is large. However, even if this is true for some people, I don’t think there are many others out there who are either willing to or capable of dramatically changing their behavior (and remaining committed to this change) after watching a single documentary. Hence, if you are one of these people for which watching Earthlings changed your life, please keep in mind that most people aren’t like you.

Assumption 3: I’ve assumed that changing behavior is costly. This seems reasonable in the domain of meat consumption and dietary change, since most people really enjoy eating meat and don’t like learning new recipes or figuring out how to replace animal products in their diet.

However, this assumption of costly behavior change means that the hypotheses I’ve described above may not carry over to other domains. For instance, the documentary Blackfish has been enormously successful at galvanizing public protest against the treatment of orcas at SeaWorld and other locations. It seems unlikely that this eruption of public anger would have happened if it were not for Blackfish, implying that the documentary has had a large causal effect. However, changing your opinion on this issue is much less costly than changing your everyday meat consumption. As a result, there is a limited amount that the anti-factory farming movement can learn from the success of Blackfish.

Summing up

So should animal advocates continue using videos, documentaries, and books to promote vegetarianism/veganism?

I think the answer is still “yes”, but I have no idea what combination of messaging strategies and sub-group targeting is likely to be most effective. My prior is that vegetarian documentaries may accelerate the meat reduction trend of sympathizers and strengthen their spillover effects, but direct effects on the general population are likely to be small. This suggests that an effective strategy would be to target sympathizers with “empowering” documentaries (like Speciesism) in order to enhance their spillover effects. Or maybe animal advocates should turn their attention towards the general population, since sympathizers are likely to decrease their meat consumption anyways and may turn out to have negligible spillover effects. Until I see strong evidence in support of one alternative over the other, I have no idea what the optimal strategy is.

Two closing recommendations:

(1) Animal advocates need to think carefully about their theory of change (e.g. which sub-groups in the population do you expect to be affected by the documentary and why? Are these people likely going to reduce their meat consumption anyways? Will these people have spillover effects on their friends/colleagues?)

(2) We need rigorous evidence on the long-term effects of vegetarian documentaries across different sub-populations. Capturing spillover effects poses more of a challenge, but it wouldn’t be difficult to conduct rigorous RCTs on the long-term effects of vegetarian documentaries. It’s just a matter of time, resources, and adequate knowledge of research design. Animal advocates are increasingly recognizing this need for evidence, though the movement has been slow to find the necessary expertise and resources to conduct these studies.

If you’re an animal advocacy group and are interested in conducting these kinds of studies, feel free to reach out to us at bmacdon@stanford.edu or gboese@sfu.ca and we are happy to talk about potential ways of collaborating.

1. My own journey into veganism started around the time I read The Ethics of What We Eat in early 2013, after which I begin avoiding products associated with what I thought were the worst forms of animal cruelty (i.e. caged eggs and beef/chicken/pork sold in major grocery stores). Since then, I’ve progressed slowly towards veganism. After moving back to Canada in September 2013 (from the UK), I began to purchase meat and eggs only from local free range farms that seemed trustworthy and I sought organic dairy products in grocery stores (under the belief that conditions were at least marginally better for animals on organic farms), though I still rarely checked product labels for dairy/egg content (e.g. salad dressing, desserts) and often made mistakes when eating out. Since moving to the US in September 2014 to start my PhD, I’ve stopped buying all meat/eggs (in part because I haven’t taken the time to search for trustworthy free range farms in the area), have cut out all dairy, and have gotten much better at checking product labels. Today, I eat 100% vegan at home, though continue to mess up from time to time when eating out (e.g. not realizing that a restaurant’s vegetarian burger comes with cheese). Moving forward, my next goal is finding ways to effectively encourage friends and colleagues to reduce their impacts on animal suffering without coming off as “holier than thou” or ostracizing them. What led me down this path towards veganism? It’s tempting to point to The Ethics of What We Eat as the causal force that got me started, but this simply raises the question of why I chose to read the book in the first place. Was I already becoming more sympathetic towards veganism and was likely going to head down this path whether or not I read the book? I have no idea.↩

2. It’s not clear whether most vegetarians have positive or negative spillover effects on others. Minson and Monin (ungated) illustrate this in a study of “do-gooder derogation” where they show that non-vegetarians rate vegetarians more negatively when anticipating that vegetarians see themselves as more moral than non-vegetarians.↩

Links we liked

By Bobbie and Greg

In an effort to post more regularly without the added effort of writing up twice is many long posts, we are going to start posting “links we liked” on a (more or less) weekly basis. (whenever we post links to papers, we’ll do our best to post un-gated links). Here goes:

1. The New York Times ran a story about an increasing numbers of doctors feeling pressure to ask their patients for donations.

2. In a recent paper (ungated) published in the QJE, Mara P. Squicciarini and Nico Voigtländer examine the role of human capital in the industrial revolution by showing how city-level subscriptions to the famous Encyclopédie in mid-18th century France predict subsequent city growth. Haven’t read it yet, but it is pretty high on my “to read” list.

3. 20 cognitive biases that screw up your decision-making, all in one chart.

4. Andrew Chang and Phillip Li tried to replicate 67 papers across 13 well-regaded economics journals. It didn’t go well.

5. A new report in the “Money for Good” research series has been released.

6. A blog post by Slate Star Codex explores the notion that meat-eaters may drastically reduce their contribution to animal suffering simply by switching from chicken to beef.

7. The Psych Report published a summary article on the psychology of poverty.

Is buying coffee from McDonald’s better or worse for animal welfare than buying coffee elsewhere? [short post]

by Bobbie

The short answer: It’s probably worse.

Obviously, chowing down on a Big Mac and a box of chicken McNuggets is not a good idea if you care about animal welfare (if you need any convincing, check out Mercy For Animal’s latest undercover investigation of Tyson Farms). Despite the temptation to bundle all McDonald’s products together under the banner of animal cruelty, it’s not immediately clear whether buying vegan products from McDonald’s — such as coffee (without cream) and apple slices — contributes to such animal cruelty.1

The case against McDonald’s coffee

On the one hand, buying coffee from McDonald’s adds to the company’s revenues, which increases the probability that McDonald’s opens additional restaurants in new locations.2 Even though McDonald’s recently announced plans to phase out battery cages for its egg supply chains in the US and Canada, this is bad news for animal welfare. An exception is if consumers in these new locations were (a) already eating meat products produced with equal cruelty and (b) the new McDonald’s restaurant does not increase the total amount of animal products consumed by local residents. Yet both of these seem pretty unlikely, especially for new restaurants in low and middle income countries where cruel factory farming practices are not as widespread. As a result, even if new McDonald’s restaurants do not increase total meat consumption in a locality, they likely increase the average animal cruelty in meat consumed by local residents.

The case for McDonald’s coffee

On the other hand, buying coffee from McDonald’s incentivizes the company to shift its marketing attention away from Big Macs and towards coffee. In other words, buying McDonald’s coffee could encourage the company to re-brand itself as a coffeehouse, and perhaps even drop the Big Mac (and other animal products) from its menu in the long-term. This would be a massive boon for animal welfare. However, this scenario isn’t very likely: McDonald’s has already been trying to build a brand around McCafe for many years, yet the Big Mac and chicken McNuggets continue to be star players in McDonald’s lineup.

The verdict

It seems that buying coffee from McDonald’s is more likely to help keep McDonald’s restaurants open than to encourage the company to shift all of its marketing attention away from animal products. So the best strategy is probably to get your coffee somewhere else.

Make note that I’ve based this conclusion off of zero empirical evidence and have made the unrealistic assumption that all coffee production has equivalent implications for animal welfare regardless of where it was sourced (e.g. Ethiopia vs. Brazil).

1. Throughout this post, I make the simplifying assumption that the production of coffee beans for McDonald’s coffee has the same implications for animal welfare (in terms of deforestation, et cetera) as coffee beans produced for any other cafe/restaurant. This is an unrealistic assumption, since we would expect coffee beans grown in different parts of the world to have varying implications for animal welfare (as a result of differences in deforestation, farming practices, et cetera). But since I don’t know anything about where McDonald’s gets its coffee compared to Starbucks and other competitors, I’ll just wave my hands and put the issue aside in this post. Instead, I’ll focus on how revenues from coffee could affect McDonald’s behavior.↩

2. Given McDonald’s recent financial difficulties, the coffee you buy might be more likely to prevent a store from closing rather than helping one open, yet the same logic applies.↩

When is behavior inconsistent with preferences?

by Bobbie

Recently, I was talking with some colleagues about how most people seem to value the future of humanity, yet do little in the present to mitigate global catastrophic risks such as climate change. There are many explanations for why we fail to act today in order to prevent future calamities (see here and here), but that’s not what this post is about. Rather, our conversation was premised on the notion that this kind of behavior reflects an inconsistency between behavior and preferences.

It’s tempting to frame many behavioral phenomena as inconsistencies between behavior and preferences, since this justifies intervening in people’s lives in order to nudge them onto behaviors that more closely align with whatever their “true” preferences are. For instance, many people continue to smoke cigarettes and eat junk food despite expressing a desire to quit, which on the surface sounds like an inconsistency between behavior and preferences.

I’ve been tempted to use a similar framing to motivate some of my own research on charitable giving and vegetarianism. For instance, a large majority of individuals claim that effectiveness is the most important attribute they consider before donating to a charity, yet very few of us actually donate to the highest impact charities. Similarly, many of us are disgusted by what happens to animals on factory farms, yet very few of us actually change our meat consumption as a result.

But do any of these situations really reflect an inconsistency between behavior and preferences? Or do these behaviors simply reveal what our true preferences are? (e.g. if I eat factory farmed steak for dinner, then the distant suffering of animals must not be that high on my priority list of preferences/values.) And if preferences are revealed by behavior, can they ever be inconsistent with one another?

Before offering a (partial) answer to this question, here are three ways in which an apparent inconsistency between behavior and preferences may not be so inconsistent after all:

(Warning: the remainder of this post is terribly under-referenced. There is an enormous literature in behavioral economics and psychology that relates to this question, which I’ll try to summarize in a future post.)

1. Inconsistency with a single preference, but consistency with the complete preference set.

At first glance, it would seem that if Jeff gorges himself on a half-dozen honey-glazed donuts despite a genuine desire to lose weight, then he is certainly acting in a way that contradicts his preference to trim down. Yet, this does not necessarily imply that Jeff’s behavior is inconsistent with his complete set of preferences. Like everybody, Jeff has many preferences, and losing weight is just one of them. In other words, perhaps his preference for chowing down on delicious honey-glazed donuts outweighs his desire to lose weight in the future, implying that his actions are entirely consistent with his preferences.

Similarly, when it comes to charitable giving, it is likely the case, in practice, that donors care more about a charity’s cause (cancer, diabetes, …) than its cost-effectiveness. If this is true, then I cannot claim that donors are behaving inconsistently with their preferences when they donate to charities with poor cost-effectiveness despite professing to care a lot about cost-effectiveness.

2. Inconsistency with the preferences of my past/future selves, but consistency with the preferences of my current self.

Second, if you survey my preferences at time t and observe my behavior at some point in the future (t+1) that turns out to contradict those initial preferences, this does not necessarily imply that my behavior at t+1 was inconsistent with my preferences at t. Instead, my preferences could have changed between t and t+1. For instance, imagine that you survey a group of people about their preferences towards eating factory farmed meat. A few weeks later, you hire an assistant to go to the homes of each person who stated a preference against eating factory farmed meat and offer them a free promotional meal consisting of a bacon cheeseburger. Chances are that some of them will take it. Is this behavior inconsistent with their preferences? Not necessarily. Although it seems inconsistent with the preferences they stated a few weeks earlier, it is possible that their preferences have changed over that time period (in addition to the mouth-watering aroma of a bacon cheeseburger, the recidivism rate for vegetarians is also quite high…).

In short, if we accept that my preferences might change over time, then it is entirely possible for my current behaviors to be inconsistent with my past/future preferences, but still consistent with my current preferences.

3. Inconsistency with my complete preference set, but consistent behavior with a salient subset of preferences.

A third nuance to consider when thinking about inconsistency between behavior and preferences is as follows: when I make a decision, I may only select a sample of my preferences with which to choose between available options. By analogy, imagine that I am choosing between breakfast cereals at the grocery store, and the cereals have ten attributes on which they differ (e.g. price, sugar content, calcium content, …). Though homo-economicus could easily select the box of cereal that maximizes her utility across the ten attributes, I certainly don’t have this kind of computational capacity. So how do I manage? (aside from giving up and buying a loaf of bread to just make toast…)

One strategy would be to sample, say, three out of the ten attributes and optimize based on these three attributes. This is one way to dramatically simplify the problem, though certainly not the only one (e.g. using informational cues from peers, using a simple heuristic like “pick only from no-name brands”, …).

Following this line of thinking, when Jeff consumed the half-dozen honey-glazed donuts in the example above, perhaps his genuine desire to lose weight was not one of the three or four preferences he based his decision upon. Hence, although it may be the case that Jeff behaved inconsistently with his complete preference set, he was not behaving inconsistently with the restricted preference set he used to make the decision.

So what does an inconsistency between behavior and preferences look like?

So far, I have described how it is possible to behave in a way that could be:

- Inconsistent with a specific preference, but not necessarily inconsistent with my complete preference set;

- Inconsistent with my past/future preference sets, but not necessarily inconsistent with my current preference set; or

- Inconsistent with my complete preference set, but not inconsistent with the restricted preference set I used to make the decision.

These three points suggest the need for caution when considering whether an observed behavior is inconsistent with preferences, and thus whether it is justifiable to paternalistically nudge someone towards behaviors that more closely align with their “true” preferences. However, this doesn’t provide an answer to the underlying question of what an inconsistency between behavior and preferences actually looks like, or whether it is even logically possible.

So, given a set of restricted preferences I use to make a decision, is it possible for my choice of behavior to be inconsistent with these preferences?

Yes.

One way for this inconsistency to occur is through an information problem. In short, when I have (or use) incomplete information about the different attributes of an object, then my chosen behavior may be sub-optimal with respect to the set of current restricted preferences that I used to make the decision.

For instance, imagine that Sarah, a recent high school graduate, is choosing between careers and the only criteria that she wishes to base her decision upon is the number of lives she will save by working in a given career. For many high school students, a career in medicine is likely to come to mind as the best way to save lives. Yet, as the organization 80,000 Hours argues, a career in medicine is likely to have a modest impact compared to a number of other careers. As a result, if Sarah goes into medicine under the questionable belief that it is the career which will maximize the number of lives she will save, then she has behaved in a way that is inconsistent with the restricted preference set she used to make the decision. To be clear, her behavior is consistent with her beliefs about which career will allow her to have the greatest impact, but inconsistent with her preferences for having the greatest impact.

As a result, where informational problems lead individuals to act in ways that do not align with the preferences they considered when making the decision, then they have behaved inconsistently with their preferences. This is similar to well-known cognitive biases — such as confirmation bias and the availability heuristic — where errors in decision-making occur when individuals systematically pay more attention to certain information when making a decision (e.g. information that supports your pre-existing viewpoint) and ignore other information (e.g. contradictory examples).

Why do we care whether behavior is consistent or inconsistent with preferences?

First, without thinking carefully about what it means for behavior to be inconsistent with preferences, it is tempting to justify all kinds of paternalistic interventions (e.g. in charitable giving, vegetarianism, environmentalism) on some vague notion of inconsistency between behavior and preferences. Upon closer inspection, many of these situations may not turn out to reflect an inconsistency between behavior and preferences, thereby necessitating other justifications for intervention.

Second, where an intervention can still be justified on other grounds, then the three main points introduced in this post can help to design more effective interventions for changing behavior. For instance, consider an individual who continues to eat factory farmed meat despite being morally repulsed by factory farming practices. If this apparent contradiction results from the fact that this person’s other preferences (e.g. craving for the taste of bacon) outweigh his moral repulsion towards factory farming, then a successful intervention will need to either find a way to fulfill both of his desires (e.g. via vegan bacon) or convince him to reconsider his preferences. In contrast, if this apparent contradiction results from his moral repulsion towards factory farming not getting selected into the restricted preference set he uses when deciding whether to eat bacon, then a successful intervention will need to find ways to “activate” this moral repulsion so that it enters his restricted preference set.

Third, thinking carefully about when behavior is inconsistent with preferences can improve our conceptual understanding of what is happening “behind the scenes” in many cognitive biases and heuristics. For instance, both confirmation bias and the availability heuristic can be understood as specific manifestations of an inconsistency between behavior and preferences that is caused by an information problem. Given the proliferation of cognitive biases and heuristics over the last decade alongside their growing use by policy-makers and businesses in the design of effective public policies and marketing strategies, finding useful ways to organize the broad landscape of biases and heuristics into general groupings is becoming more and more needed.

Metaphors for Charitable Giving

by Greg

On this blog, and in our day-to-day lives, we spend a lot of time talking to others about charitable giving. Ideally, we’d like to find ways to encourage others to give more, and give better.

Metaphors are one useful tool for talking about charitable giving.

For example, philosopher Peter Singer encourages us to give more to charity using a simple yet compelling metaphor about a drowning child:

“To challenge my students to think about the ethics of what we owe to people in need, I ask them to imagine that their route to the university takes them past a shallow pond. One morning, I say to them, you notice a child has fallen in and appears to be drowning. To wade in and pull the child out would be easy but it will mean that you get your clothes wet and muddy, and by the time you go home and change you will have missed your first class. I then ask the students: do you have any obligation to rescue the child? Unanimously, the students say they do. The importance of saving a child so far outweighs the cost of getting one’s clothes muddy and missing a class, that they refuse to consider it any kind of excuse for not saving the child… Once we are all clear about our obligations to rescue the drowning child in front of us, I ask: would it make any difference if the child were far away, in another country perhaps, but similarly in danger of death, and equally within your means to save, at no great cost – and absolutely no danger – to yourself? Virtually all agree that distance and nationality make no moral difference to the situation. I then point out that we are all in that situation of the person passing the shallow pond: we can all save lives of people, both children and adults, who would otherwise die, and we can do so at a very small cost to us: the cost of a new CD, a shirt or a night out at a restaurant or concert, can mean the difference between life and death to more than one person somewhere in the world.”

—The Drowning Child and the Expanding Circle (Singer, 1997)

In addition to giving more to charity (which for the average person, is probably quite feasible), it is also important to give better. That is, as much as possible, we should try to give our money to effective charities serving high-impact causes.

One popular metaphor for encouraging better giving is to frame charitable giving like a economic or business transaction.

For example, Holden Karnofsky of GiveWell considers whether we should compare the act of donating to charity to that of buying a printer. (See also, Charity “Shoppers” vs. Charity Investors; Karlan, 2013). Think of the steps we go through when we want to buy a printer. We probably begin by searching the internet to compile a broad list of options. We then carefully read reviews and recommendations, and weigh the pros and cons of our various options. Finally, we choose a printer that we feel gives us the most bang for our buck.

“If you really care whether your printer works, you’re willing to put in some time and read some boring stuff before you buy… If you really care about helping others, don’t demand any less.”

—I Just Bought a Printer (Karnofsky, 2007)

Now, I generally like the economic or business metaphor. It’s simple. It’s relatively intuitive. And in my experience, it’s useful for convincing some people to think about giving better.

That said, I’d like to discuss two potential shortcomings of this metaphor.

1. One potential shortcoming of a business metaphor is that it may erode giving motivation. We like to help other people. It makes us happy. (See, for example Andreoni, 1990 or Dunn, Aknin & Norton, 2008). I wonder, however–and this is of course an empirical question–whether people need to explicitly view their charitable giving as a prosocial (vs. business) transaction in order to experience the emotional benefits. Thus, though it’s intended to encourage people to give better, a business metaphor may in fact reduce the likelihood that people even give at all.

2. A second potential shortcoming of a business metaphor is that some people really dislike thinking about charitable giving in largely economic or business terms. Psychologist Phillip Tetlock and colleagues attribute this aversion to a moral opposition to reducing human life to mere dollars and cents—a so-called taboo trade-off (Tetlock et al., 2000). I wonder–and again, this is an empirical question–whether using a business metaphor risks offending and thus turning away potential donors from a conversation about better giving.

The moral curse of dimensionality

by Bobbie

As we increase the number of moral ideals that we use to evaluate the moral character of individuals and corporations, it becomes almost impossible for anybody to meet our minimum threshold for morally acceptable behavior on every ideal. This “moral curse of dimensionality” is a product of three phenomena: (1) diverse moral ideals in society; (2) disagreement over the relative importance of these ideals; and (3) a willingness to label others as “moral monsters” because they fail to live up to one or more ideals. The moral curse of dimensionality raises many interesting empirical questions, several of which I introduce at the end of this post.

Like you, I have moral ideals that I try (and regularly fail) to live up to in my everyday life, such as donating to the most effective charities and not consuming factory farmed animal products. For others, these ideals might include organic composting, tipping at least 15% at restaurants, buying only fairtrade coffee, regularly attending church, giving up one’s seat on the bus for a pregnant woman, et cetera.

Given that we live in a society with diverse morals, not all of us agree on which ideals are most important or what the “correct” behavior is for a given ideal. To help make sense of our moral judgments, Jonathan Haidt and his colleagues divide moral values into six major “moral tastebuds” on which individuals differ: care/harm, fairness/cheating, liberty/oppression, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation. Yet, each of these categories can be broken down into many more specific moral ideals, giving rise to an enormous range of potential ideals by which others might evaluate your moral character.

Moral diversity is a good thing for society. It allows for freedom of choice and regular public debate about the kinds of morals ideals we wish to value. Yet, as we increase the number of moral ideals used to evaluate others, it becomes almost impossible for any given person to meet your minimum threshold to be considered a “morally acceptable” person.

In short, the greater number of moral ideals you value and use to evaluate the moral character of others, the more difficult it becomes to give anybody a passing moral grade. This “moral curse of dimensionality” is particularly problematic for politicians, celebrities, corporation, and others who face constant public scrutiny. As a result, when you evaluate the moral character of others across many ideals, it becomes increasingly difficult to justify voting for any political candidate, shopping at any store, or liking any movie without violating one or more of your own moral ideals.

These two satirical videos make the point far better than I can: here and here.

Statistics and morality

The curse of dimensionality is a well-known concept in mathematics and statistics. Put simply, as the number of dimensions of a problem increases, it becomes dramatically less likely that two observations are similar to each other on ALL dimensions. For instance, in a university of 15,000 students, you would have no trouble finding many students that have birthdays in the same month as you. Yet, as you add more and more dimensions to the problem (e.g. year of birth, hair color, favorite movie, et cetera), it becomes very unlikely that any student is similar to you on every dimension.

Turning back to morality, imagine some point in one-dimensional space, representing the action of a person on one moral ideal (e.g. amount of factory farmed meat consumed this year). Let’s call this person John. A value of 1 represents “morally perfect” behavior by John on this dimension (i.e. 0kg of factory farmed meat consumed so far this year), while a value close to 0 represents “immoral” behavior (e.g. 100kg of factory farmed meat so far this year). As long as John exceeds some arbitrary minimum threshold (e.g. 0.5, representing 10kg of factory farmed meat consumed so far this year), then he meets your criteria to be labelled as morally acceptable.

However, as we add more dimensions to this problem (e.g. is John a generous tipper at restaurants? Does he buy fairtrade coffee? …), it becomes increasingly less likely for John to meet this minimum threshold on every moral ideal under consideration.

This curse of dimensionality is illustrated below using simulations of 10,000 people. For each simulated person, I randomly select a point between 0 and 1, representing a continuum of immoral to moral behavior on a single dimension. I repeat this 40 times for each person, providing 40 different moral dimensions on which each person may be considered moral or immoral. I then set a minimum threshold of 0.5, such that if a person has a value less than 0.5 for a given dimension then they are considered immoral on that dimension.

Each dot in the figure below shows the percentage of people that meet this minimum threshold according to the number of dimensions under consideration. When considering only one dimension, a majority of the 10,000 simulated people are “morally good” according to this criteria. As we increase the number of dimensions under consideration, however, this number decreases rapidly.

The moral curse of dimensionality implies that we should be more humble when judging the moral character of others. Next time you observe someone make a relatively minor moral transgression (e.g. eating a factory farmed steak, throwing a recyclable container in the garbage, or making an inconsiderate remark), be careful not to pass judgment on their moral character as a whole and think carefully about whether they might surpass you on other moral dimensions (e.g. maybe they took the Giving What We Can pledge to donate at least 10% of their annual income to the most effective charities fighting global poverty).

Empirical questions

Finally, the moral curse of dimensionality raises a number of important empirical questions:

- First, how many moral dimensions do we use to evaluate the moral character of others? Do we judge the moral character of others on a greater number of moral dimensions today than we did in the past?

- Second, does the average person consistently use the same dimensions to judge the moral character of others? Or does it depend on context and the identity of the person being judged?

- Third, how many moral dimensions do we use to evaluate our own moral character? Do we evaluate others using the same moral dimensions and criteria we use to evaluate ourselves?

- Fourth, how do we form preferences about which moral dimensions are most important to us? How much do these preferences vary over time?

- Fifth, how does the moral curse of dimensionality alter the behavior of individuals and corporations that are in the public eye? Does it induce risk-averse behavior, such that politicians and celebrities avoid taking stances on important issues due to a fear of fierce moral criticism?

Quantifying SPSSI 2015: What policy issues do psychologists care about?

by Greg

On June 20-21, the Society for the Psychology Study of Social Issues (SPSSI) organized a special conference in Washington, DC for psychologists to share research linking psychological science and public policy.

I get the sense that, for many psychologists, the ultimate motivation for entering the policy realm is to help people. Obviously, we would prefer work on all policy issues. In reality, however, that is simply not possible. We must pick and choose. We must prioritize. (Or maybe accept more graduate students).

Assuming we would all prefer to help as many people possible, what topics should we focus on?

What should we prioritize?

This is certainly a very difficult question to answer. (Though see, for example, the work of the Copenhagen Consensus Centre; click here for a brief summary TED Talk). Even if we can’t answer that admittedly difficult question, it can still be useful to simply take stock of what topics psychologists are currently studying, and then ask a slightly easier question: Could we be doing better?

There was a lot of diversity in the range of policy topics covered at this conference. Below, I have very roughly quantified the distribution of presentations (talks, posters, discussion groups, policy briefs), based on the titles and abstracts featured in the conference program. To be clear, this is not a rigorous analysis. In more than a few cases, a particular talk or poster was clearly relevant to more than one policy issue; in such cases, I coded the presentation according to whichever policy topic I thought was most salient. Also, my analysis excludes many (19) presentations that focused generally on applying psychology to public policy. These presentations were great, but often served a professional development purpose, and thus did not focus on a particular policy topic.

So, according to the SPSSI 2015 conference program, what policy topics do psychologists currently prioritize?

The top 5 most common policy topics were:

- Minorities’ academic engagement (e.g., “Targeting Stereotype Threat Reduction to Increase Participation in STEM Fields”),

- Intergroup relations/inequality (e.g., Improving Minority-Minority Relations: How Can Social Psychological Research Inform Policies”),

- Military and veteran issues (e.g., “Veteran-Guided Community Readjustment and Reintegration”),

- Criminal offenders rehabilitation (e.g., “Unemployment, Suicidal Ideation, and Depression Among Former Jail Inmates”), and

- Sexual minority populations (e.g., “The LBTQ Adolescent Health Experience: An Exploration into Provider-Patient Interaction”).

Now, imagine policy makers had a sudden change-of-heart, and decided to actually listen to psychologists for a change. Imagine further that we were able to work with policy makers to successfully translate our best recommendations about these topics into real-world interventions. Finally, imagine we were able to completely solve the problems associated with each of the 5 topics listed above. How many people do you think we would we have helped?

Lots, probably. These are all important issues, and solving them would undoubtedly contribute to improving the world. The key question, however, is whether we could do better. Could we have helped more people if we focused on different policy topics?

For example, many of the topics featured at this conference focused primarily on helping people living in the US. However, there are around 1 billion people living in other parts of the world who face a myriad of problems associated with extreme poverty. If we are serious about helping as many people as possible, fighting global poverty might be a pretty good place to start. Eventually, I’d like to write a bit about what topics I think we should prioritize. In the meantime, however, I’d simply encourage each of us to reflect critically about the relative importance and potential contributions of our various policy interests.

China plans world’s largest supercollider. Meanwhile, in political science …

by Bobbie

One of the things we will be doing a lot on this blog is making comparisons between disciplines and examining what social scientists can (and cannot) learn from the natural and physical sciences.

To get things started, I can’t resist highlighting how political science is at such a dramatically different stage of maturity compared to its distant relatives in the physical sciences:

Back in September, China announced plans to build the world’s largest supercollider (link). Meanwhile, political scientists continue to squabble over whether political science is “relevant” (link).

Do community giving days increase or displace charitable giving?

by Bobbie

Earlier this month, Give Local America held its second annual community giving day across the US. The Chronicle of Philanthropy summarizes the event as follows:

“Organizations participating in the second year of Give Local America, held May 5-6, raised $68.5 million over about 24 hours, 29 percent more than last year’s inaugural event. More than 9,000 nonprofits participated, building on the growing trend of local giving days, which harness the support of community foundations and local United Way branches to encourage giving to local nonprofits.

As with other giving days, the event cultivated new donors: 35 percent of donors indicated it was their first gift to a particular charity.

Human services groups received 28 percent of the donations, followed by education and then arts and culture groups, which received 19 percent and 16 percent respectively.”

Similarly, on June 6 2015, the 100in1Day festival is being held across four Canadian cities (Vancouver, Toronto, Halifax, Hamilton), inviting community members to come out and participate in small initiatives to spark change.

My early thoughts on these local giving and civic engagement events:

1. Do community giving events merely displace other charitable donations?

35 percent of donors at Give Local America’s community giving day said that it was their first gift to a particular charity, which means that 65 percent of donations came from individuals who had already donated to that particular charity. For this 65 percent, did the event actually encourage them to give more to the charity than they otherwise would have? It’s easy to imagine that some donors simply substituted a community giving day donation for their Christmas donation. On the other hand, it’s entirely possible that the event either had no substitution effect or even had a positive effect on future giving by making recurring donors more personally connected to the charity.

A charity could get some leverage on this question by comparing the subsequent donation records of existing donors who made a donation during the community giving day to those who did not.

Second, among the 35 percent of new donors to a particular charity, we don’t know whether these individuals were regular donors to other charities or whether they were new to the whole charitable giving scene. If it’s the former, then I have similar concerns about whether community giving days simply displace donations to other charities or whether they help to build a “giving identity” that encourages donors to give more in the future.

2. Do these kinds of events risk creating a “give local” movement?

Giving to charity is a great thing to do, whether it’s to a local, national, or international charity. As of now, it seems that community giving days and other local giving events are simply aimed at getting people to come out and give more, rather than making the argument that local charities are somehow more worthy of charitable donations than national or international charities.

However, if these community giving events ever begin to advertise that local charities are somehow more worthy of charitable donations than national or international charities (resembling the “eat local” movement), then this would be a major concern. For organizations such as GiveWell and Giving What We Can who are devoted to finding the most impactful charitable giving opportunities, their top charity recommendations are non-profits doing international work (e.g. GiveDirectly, Against Malaria Foundation).

Give Local America’s next Community Giving Day is May 3, 2016. If anyone can convince the organizers to collect more data to answer the questions above, that would be great.